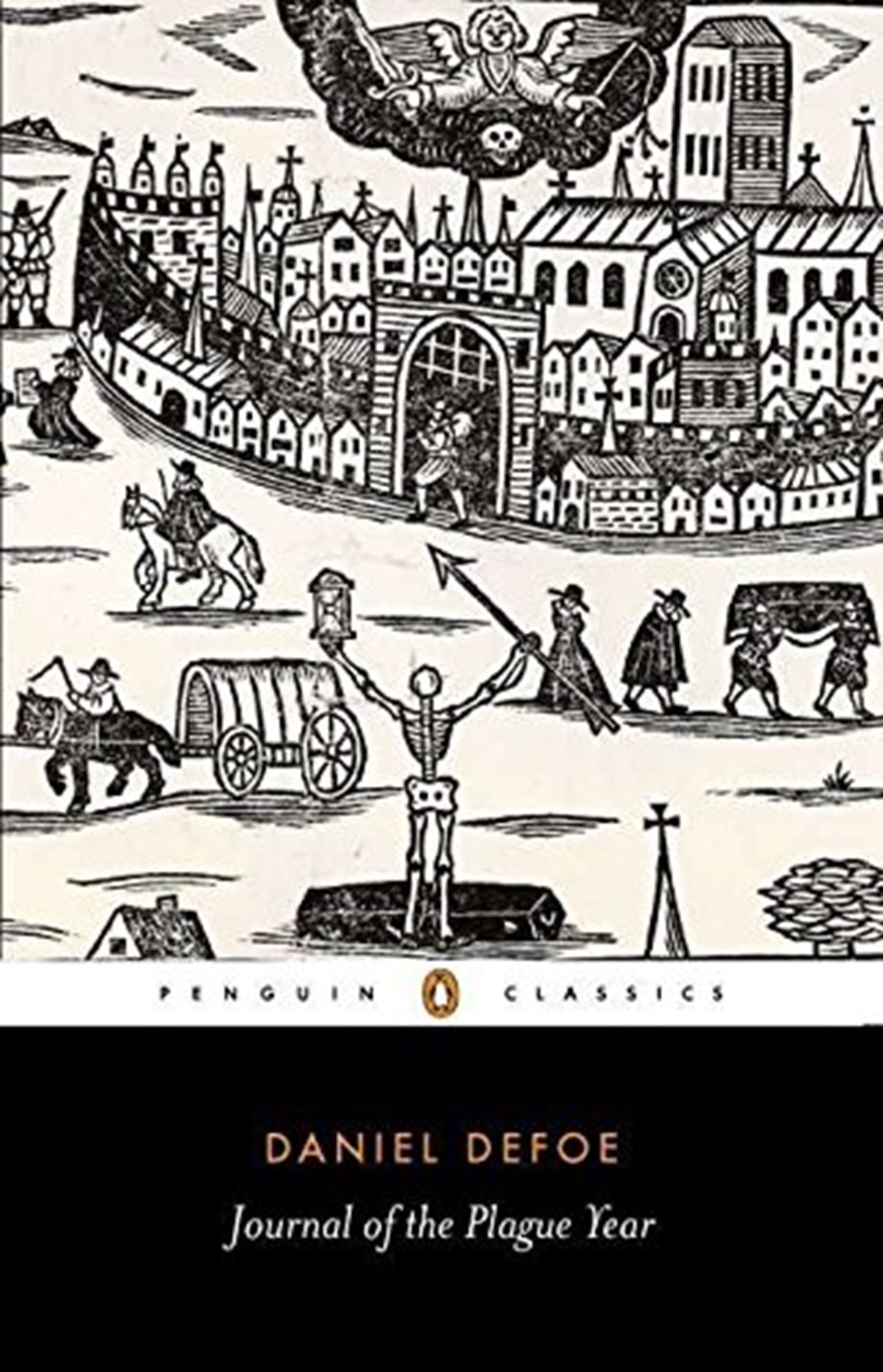

For writers, it’s the chance to explore a world in which fantasy and reality have swapped places. So what draws writers and readers to such a grisly subject? Something not entirely wholesome, perhaps. Plague literature is a genre in its own right. That was when the plague flared up all over again. The most dangerous time, he reports, was when people thought it was safe to go out. There’s one thing in particular governments might learn from the book – and it’s tough. Throughout the journal, HF tells us he hopes his experiences and advice might be useful to us. ‘Lord, have mercy on London.’ Contemporary English woodcut on the Great Plague of 1665. By the time the idea had occurred to the rest of the population, you couldn’t find a horse for love or money. Near the start of the outbreak in 1665, the court and those with money or homes in the country fled London in droves.

They were more likely to suffer ill health in the first place, as now, and they had no means of escape.

They lived, as they do now, in more cramped conditions, and were more susceptible to taking bad advice. Plague affected the poor disproportionately. For all his uncertainties, he is adamant about one thing. When Prince Charles and Boris Johnson fell ill recently, we were told the virus “ does not discriminate”. Yet he hears plenty of stories about victims breathing into the faces of passers by, or infected men randomly hugging and kissing women in the street. Is it possible, he asks, that there are some people so wicked that they deliberately infect others? He just can’t square the idea with his more kindly view of human nature. He is a devout Christian, but the stories that worry him most are the ones that still shock everyone today, regardless of their beliefs. Later, exhibiting one of his less appealing traits, he is gratified to hear that they all caught the plague and died. At one point he confronts a group of rowdies and gets a torrent of abuse in return. HF is appalled by those who opened up taverns and spent their days and nights drinking, mocking anyone who objected. After all, they might be locked in their homes to catch the disease and die.

Reporting was difficult, partly because people were reluctant to admit there was an infection in the family. Still, it was impossible to be sure who had died directly of the disease, just as in the BBC news today we hear people have died “with” rather than “of” COVID-19. They charted deaths by parish, giving a picture of how the plague was moving around the city. HF becomes obsessed with the weekly mortality figures.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)